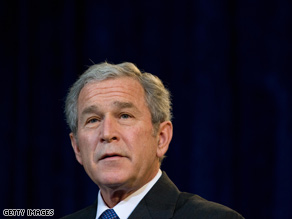

Congress Has Enough Evidence for an Impeachment Inquiry

Detractors of an impeachment inquiry by the House judiciary committee into whether President George W. Bush has committed impeachable offenses contend that no questions should be asked until conclusive incriminating evidence is either volunteered up by the suspects themselves or appears before them by spontaneous combustion. In other words, they say, no inquiry should commence until proof of the president's guilt has been unearthed—proof which would, of course, make the inquiry superfluous! The Watergate investigation that dethroned President Richard M. Nixon would never have been launched under such an Alice in Wonderland standard of proof, because it began with nothing more than two obscure figures, E. Howard Hunt and Gordon Liddy, known to have both White House connections and associations with the Watergate burglars.

Article II, Section 4 of the Constitution stipulates: "The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors." Article I, Section 2 endows the House of Representatives with "the sole Power of impeachment." And Article I, Section 3 entrusts the trial of impeachments to the Senate and requires a two-thirds vote for conviction.

The impeachment process thus envisions the House as operating like a sort of grand jury and the Senate like a trial jury. The House investigates to determine whether evidence can be marshaled to prove impeachable high crimes and misdemeanors. And if the answer to that question is affirmative, the House then decides whether to vote articles of impeachment. That judgment represents a collection of prudence, politics, and law akin to prosecutorial discretion. If articles are approved, a trial is held before the Senate with the chief justice of the United States presiding if the president is the accused.

The House does not require, nor should it await, proof beyond a reasonable doubt of misconduct. To wait for such proof subverts the whole purpose of an impeachment inquiry.

According to the Founding Fathers, impeachable offenses are crimes against the Constitution, which may or may not include violations of the federal criminal code. As Alexander Hamilton elaborated in Federalist 65, impeachment cannot be "tied down" by "strict rules, either in the delineation of the offense" by the House, or "in the construction of it" by the Senate. James Iredell sermonized to North Carolina's ratification convention that "giving false information to the Senate" was characteristic "of great injury to the community" that would warrant impeachment. False information distorts legislative judgments and makes a farce of congressional oversight to detect lawlessness or maladministration by the executive branch.

Articles of impeachment were voted against President Nixon by the House judiciary committee for flouting his constitutional obligation to "take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed" and for refusing to comply with congressional subpoenas issued in conjunction with the impeachment inquiry. The twin articles of impeachment against President William Jefferson Clinton accused the chief executive of perjury and obstruction of justice in violation of his duty to enforce, not sabotage, the law.

Impeachment precedents fortified by the original intent of the Constitution's makers provide ample justification for a House judiciary committee impeachment inquiry targeting President Bush for—among other things—multiple criminal violations of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act and frustration of legitimate congressional oversight with preposterous claims of executive privilege.

FISA makes it a federal felony for the president or vice president to "intentionally engage … in electronic surveillance [to gather foreign intelligence or otherwise] under color of law except as authorized by statute." A companion provision provides that the FISA's procedures are the "exclusive means" for conducting electronic surveillance. After a leak to the New York Times published on Dec. 16, 2005, Bush confessed that in the aftermath of 9/11, he instructed the National Security Agency to flout FISA by targeting Americans for electronic surveillance on his say-so, a spying program styled the "Terrorist Surveillance Program." The president's apparently criminal spying continued until at least January 2007—or for more than five years—when Attorney General Alberto Gonzales declared that FISA warrants, whose nature remains classified, would replace the TSP. (The attorney general maintained, however, that Bush continued to be crowned with Article II powers to ignore the warrant requirement and to do so secretly whenever he wished.)

The president has labored successfully through legal technicalities such as a lack of "standing" or the "state secrets doctrine" to circumvent a definitive judicial ruling on the legality of the TSP. One could have been quickly obtained if the attorney general had submitted in an application for a FISA warrant evidence obtained under the TSP. In determining whether probable cause had been established, the FISA court would have been required to decide whether the TSP was legal and its intelligence admissible.

An impeachment inquiry should demand the president's defense of the TSP's violations of FISA's criminal prohibition for many years. Soon-to-be-former Attorney General Gonzales has asserted that crafting a legal rationale has been a dynamic, not a static, exercise. The committee should insist on access to the attorney general's legal evolution from the inception of the TSP. The inquiry should also demand to know, among other things, how many Americans were targeted by the TSP, how they were selected, what was the intelligence yield from the FISA violations, and what safeguards were erected to prevent misuse of the intelligence collected. Moreover, the committee should demand an explanation of why statutory amendments to FISA to correct perceived deficiencies were bypassed in favor of flouting the law.

This information is necessary before the committee can assess whether mitigating factors partially justified Bush's criminal violations of FISA. During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln, in explaining to Congress his unilateral suspension of the Great Writ of habeas corpus, rhetorically asked whether a republic must inescapably be too strong for the liberties of its people or too weak to maintain its existence. The committee should similarly explore whether in the aftermath of 9/11, Bush was confronting such a dilemma.

An impeachment inquiry should further examine Bush's repeated assertions of executive privilege to operate a secret government eavesdropping program. He has refused to disclose to Congress details of the TSP redacted to protect intelligence sources and methods. Other spying programs that have not yet leaked to the media remain secret. The president has additionally prohibited current and former White House aides and advisers, including Karl Rove, Harriet Miers, and Joshua Bolten, from appearing before Congress. Their testimonies have been sought to probe suspected perjury or obstruction of a congressional investigation by Gonzales and the manipulation of U.S. attorneys and civil servants in the Department of Justice to advance the political fortunes of the Republican Party. If Bush's conception of executive privilege had been asserted by Nixon, the Watergate investigation starring former White House counsel John Dean would have been stillborn.

If what Bush has said and done falls short of warranting an impeachment inquiry, then impeachment of the president has become a virtual dead letter.

Bruce Fein is a constitutional lawyer at Bruce Fein & Associates and chairman of the American Freedom Agenda. He is author of the forthcoming book Constitutional Peril: The Life and Death Struggle Over the Constitution and Democracy.

Article URL: http://www.slate.com/id/2173106/